By the way, what’s a AA?

A taxonomy of the video game production scope

You've probably heard terms like “AAA”, “AA”, “indie”. Maybe you’ve even heard of "III" or, brace yourself, AAAA.1 But ask ten people on what those mean and you'll certainly get ten different answers. While some blogs ventured to define criteria, they remain ballpark figures.2 Let's be honest, that non-definition might be enough for quick chats. We all understand that a ‘solodev’ title has a reduced scope compared to an ‘AA’ production, and we all agree that GTA VI will likely be the most ambitious ‘AAA’ game ever made. Then, can't we just go home and be happy with it?

The problem is: at HushCrasher, we believe that a serious discussion of the video game industry, from its financial health to its creative trends, requires a common framework. That's why we had to go down the rabbit hole of finding a clear and objective method to classify games, and finally conclude that using the word "indie" should be banned.

Guess Who?

HushCrasher is a scream of rage against .·✩·.¸¸.·¯⍣✩intuition✩⍣¯·.¸¸.·✩·. -based theories. Therefore, any vibe-analysis is clearly out of the question. If only there were a way to identify games that share a similar scope without making any preconceived assumptions. The good news is there is a whole strand of data science dedicated to finding groups of similar elements based on their characteristics, known as clustering.

First, we've gathered data from all games published on Steam since 2006, and enhanced it with credits from Mobygames, a crowdsourced database on games and the people who made it. Second, we looked at characteristics that could serve as indicators of a game's scope (length and diversity of the credits, disk usage, number of available languages, etc.). Finally, we ran a clustering algorithm to identify distinct game categories, as detailed in our research paper.

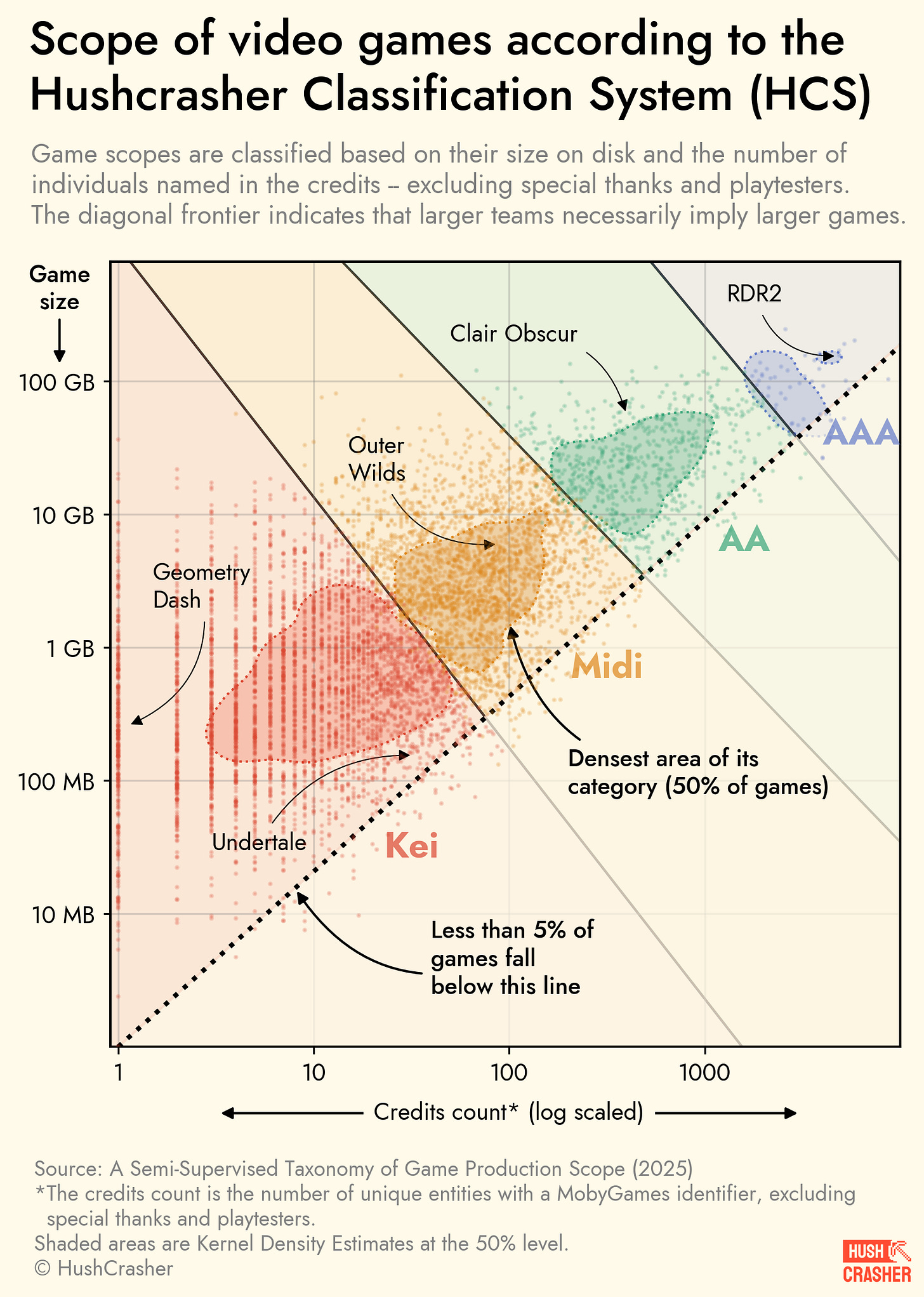

It turns out the main factors to classify a game are the length of its credits and its disk size, far outweighing all the other metrics! And it makes sense, those two measures are tightly linked to the amount of work that was involved in making the game. Based on our methodology, we identify 4 distinct categories of games:

- The Kei games. Those are what many would call 'solodev' games. Popular examples are Undertale, Papers Please, or Terraria. While they are often the work of a lone creator, they can also be made by a couple of friends or siblings. The term "Kei" captures this sense of small-scale, in reference to Japan's famously tiny car.

- The Midi games. Those are made by small and medium studios. Think of games like Hades and Valheim. These are in between the intimacy of Kei games and the larger ambition of AAs.

- The AA games. This is the entry point for multi-million-dollar budgets. They are developed by large teams with hundreds of credited individuals, including contractors, and a growing number of middle management and support staff (HR, finance, etc.).

- The AAA games. Here, sky's the limit. Let's just say that if a few thousands of people worked on the game and you had to buy a new SSD to install it, chances are it's a AAA.

Together they form the Hushcrasher Classification System™ 1.0 (HCS). It's a tool designed to cut through the noise, categorizing games by the length of their credits and the game size. And just like that, we've invented 2 new labels for game categories. Do we hope they go mainstream? Hell yeah! If you wish to classify a game by yourself, follow our guide.

Now that you know who's who let's see what we could learn from the last decade to better understand what's coming next.

Indie and the Temple of Doom

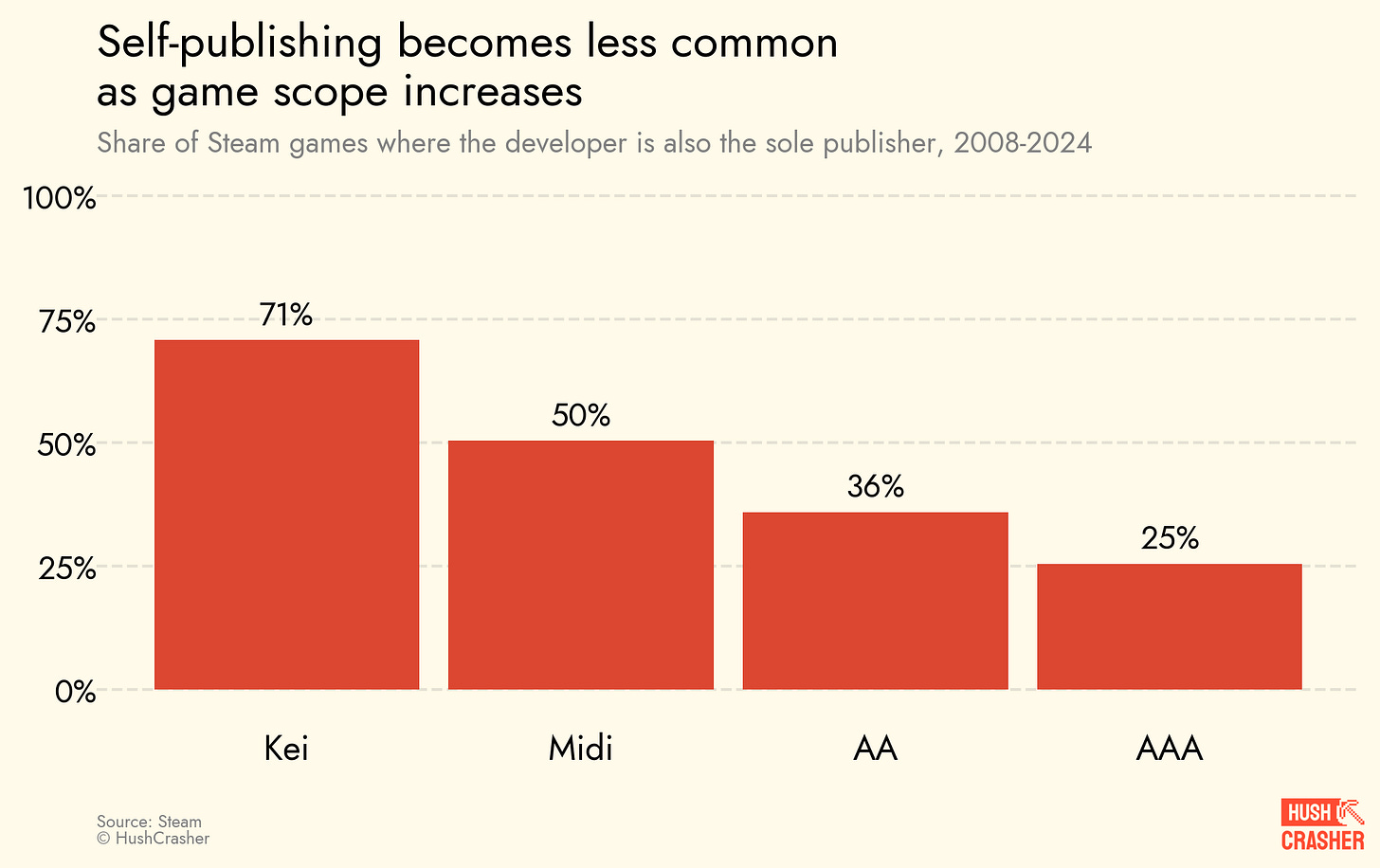

"Why are there no Indie category?" you may ask. Because one could award "indie" the most confusing term ever in video games. While everyone seems to agree that solodev, AA, and AAA largely refer to game scopes, this is not the case for indie games. When speaking of it, people mix in lots of others characteristics: aesthetics ("indie vibe"), creative or financial freedom, team size, IP, and intention (making games "for the sake of it").3 A good example of this is the recent confusion around Dave the Diver. For instance, if you think that 'indie' means being self-published, you might be surprised to learn that:

A quarter of AAA games are self-published (e.g. Cyberpunk 2077, Assassin's Creed, and GTA)

At least a quarter of Kei & Midi games, which are the types of games people would typically call 'indie', have a publisher.

We told you, this whole 'indie means self-published' is just flawed.

The Indiepocalypse Keipocalypse

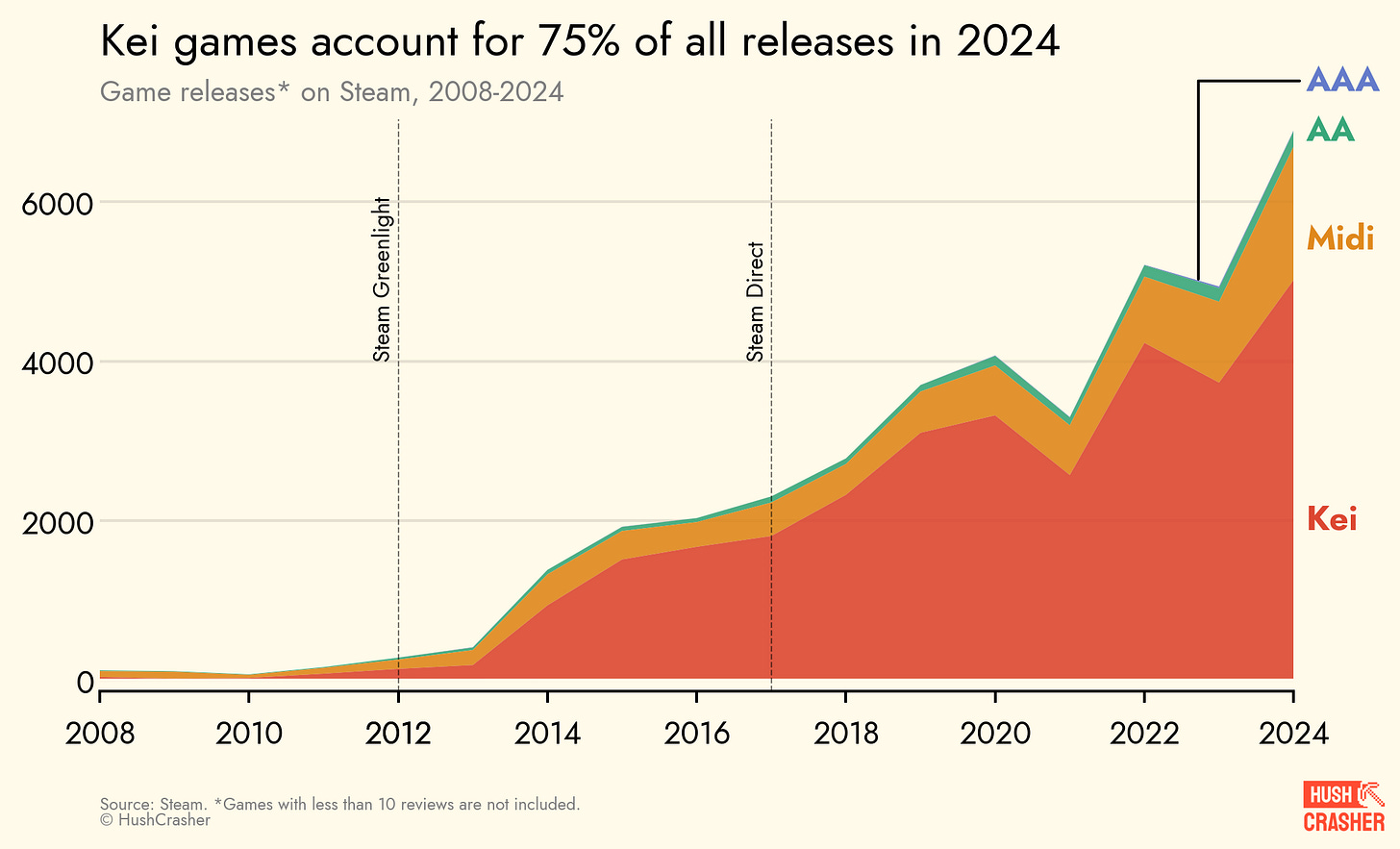

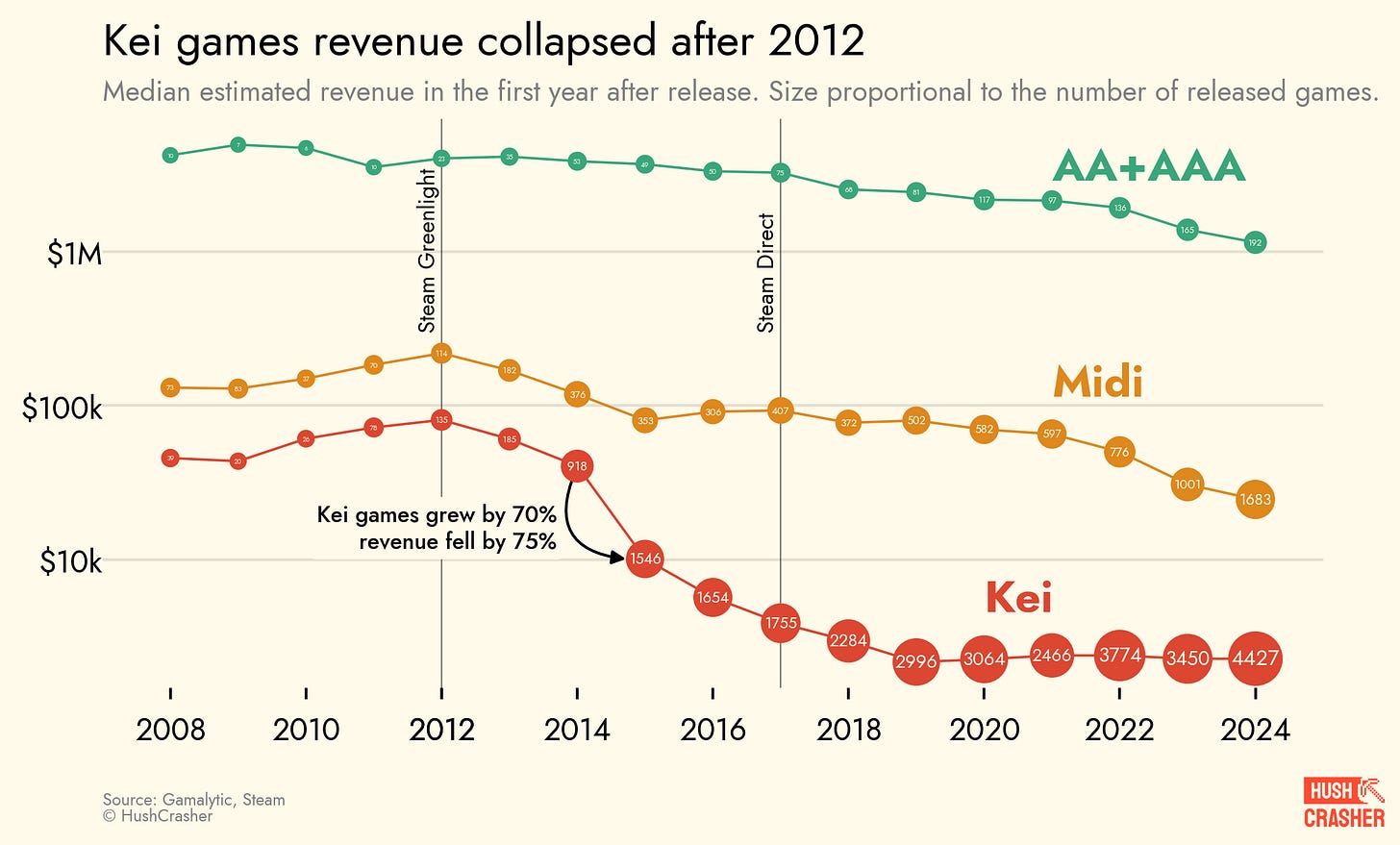

In the last decade, it became possible for anyone to develop and publish a game - since the Steam Direct program in 2017, getting your game on the platform only requires a $100 fee. Naturally, competition grew fierce. We've seen a massive surge in Kei games, sometimes referred to as the indiepocalypse. The number of Kei game releases has been multiplied by 16 in a matter of years. Today, they account for more than 7 out of 10 releases. This is without a doubt the greatest transformation in this industry over the past decade. Meanwhile, the share of A-games hasn't diminished, representing a stable 3% of all published games.

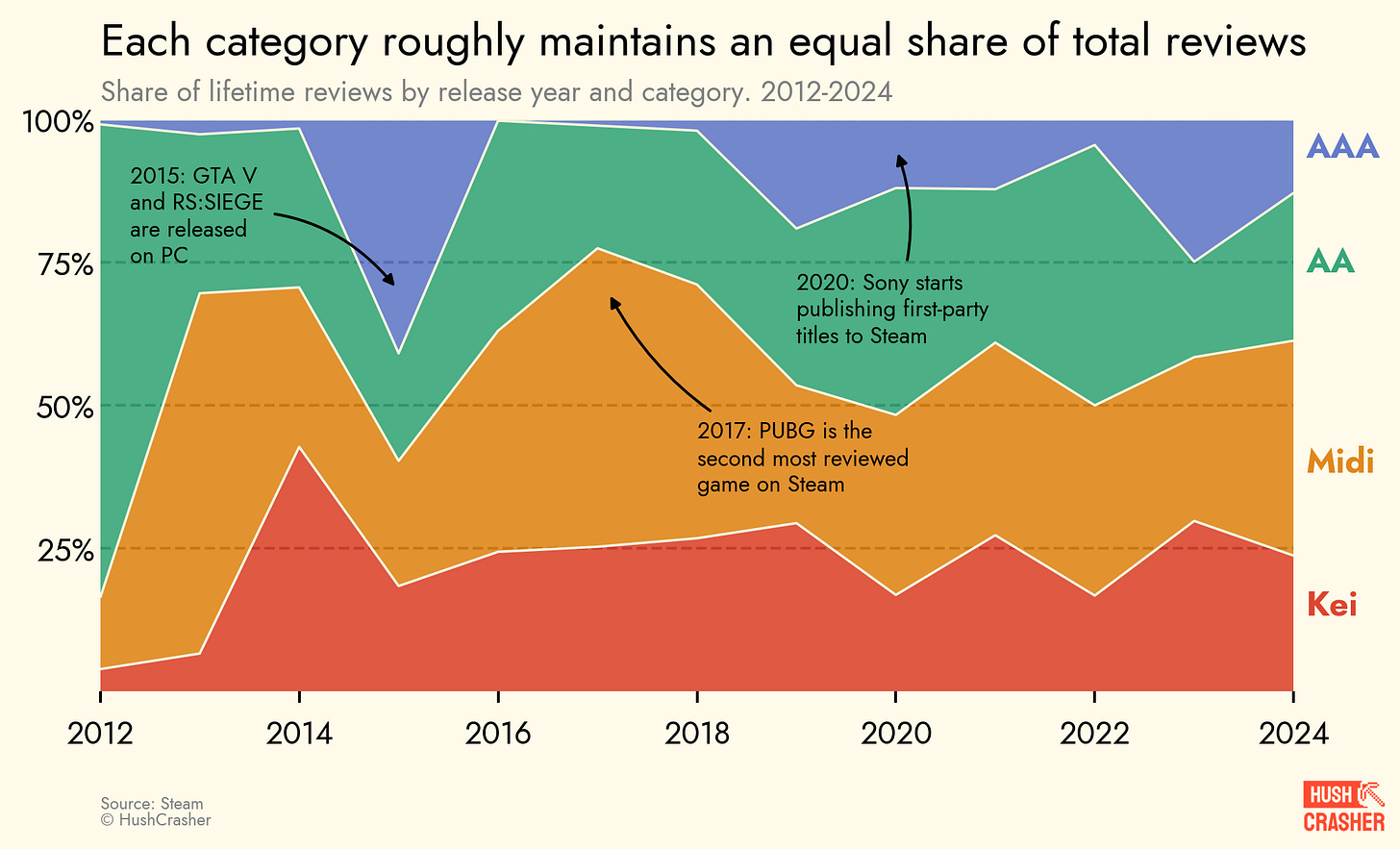

Sure, there are more Kei games available, but are people actually buying them? The truth is: the shock was so important that the market simply couldn't absorb it. Despite making up 75% of new releases in 2024, the share of reviews (a good proxy for sales) allocated to Kei games hasn't changed for a decade. It remained remarkably stable, never getting above ~25%.

Of course, not all games are created equal. Many are never played; in fact, 4 out of 10 games released in 2024 haven't even received ten reviews.4 Some are likely bad, but most are certainly just less visible, lost in the overwhelming flood of competing titles. This is where the real picture comes in: Kei games have definitely swamped the market, but they haven't exactly taken away the sales. If there's competition, it’s among Kei games themselves. What we're seeing is an almost perfect split: each segment claiming a quarter of the market.

With a flood of new games and no change in market share, the median revenue per game collapsed by an astounding 97%—from $80k in 2012 to below $3k in 2018.5

On a more positive note, the "Keipocalypse" is not just about destruction. The very same factors that led to market saturation—lower entry costs and facilitated distribution—have also led to a remarkable diversification of the industry. Developers can now create titles for very specific niches, knowing that even a few hundred sales can make the project worthwhile.

Legend of Leagues

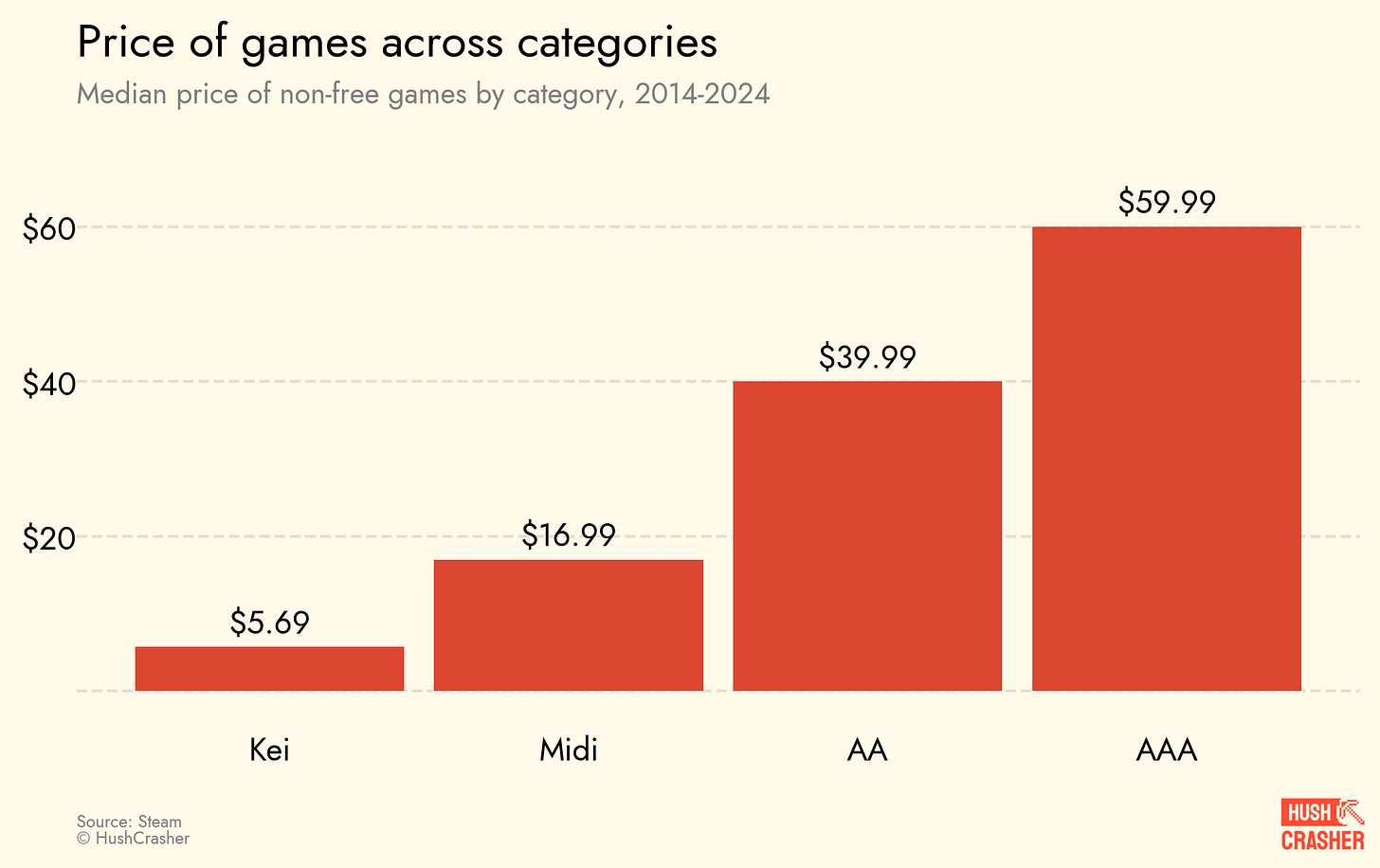

Players won't stop buying AAA because of the latest Kei game. In fact, they are probably not even the same players at all (and this might be a story for another time). This segmentation is also reflected in their retail prices, which are almost evenly spaced between each category. A Kei game costs only a few bucks, around $17 for Midi games, $40 for AAs, and $60 for most AAAs available on Steam.

Why don't we get more Open World-Platformers

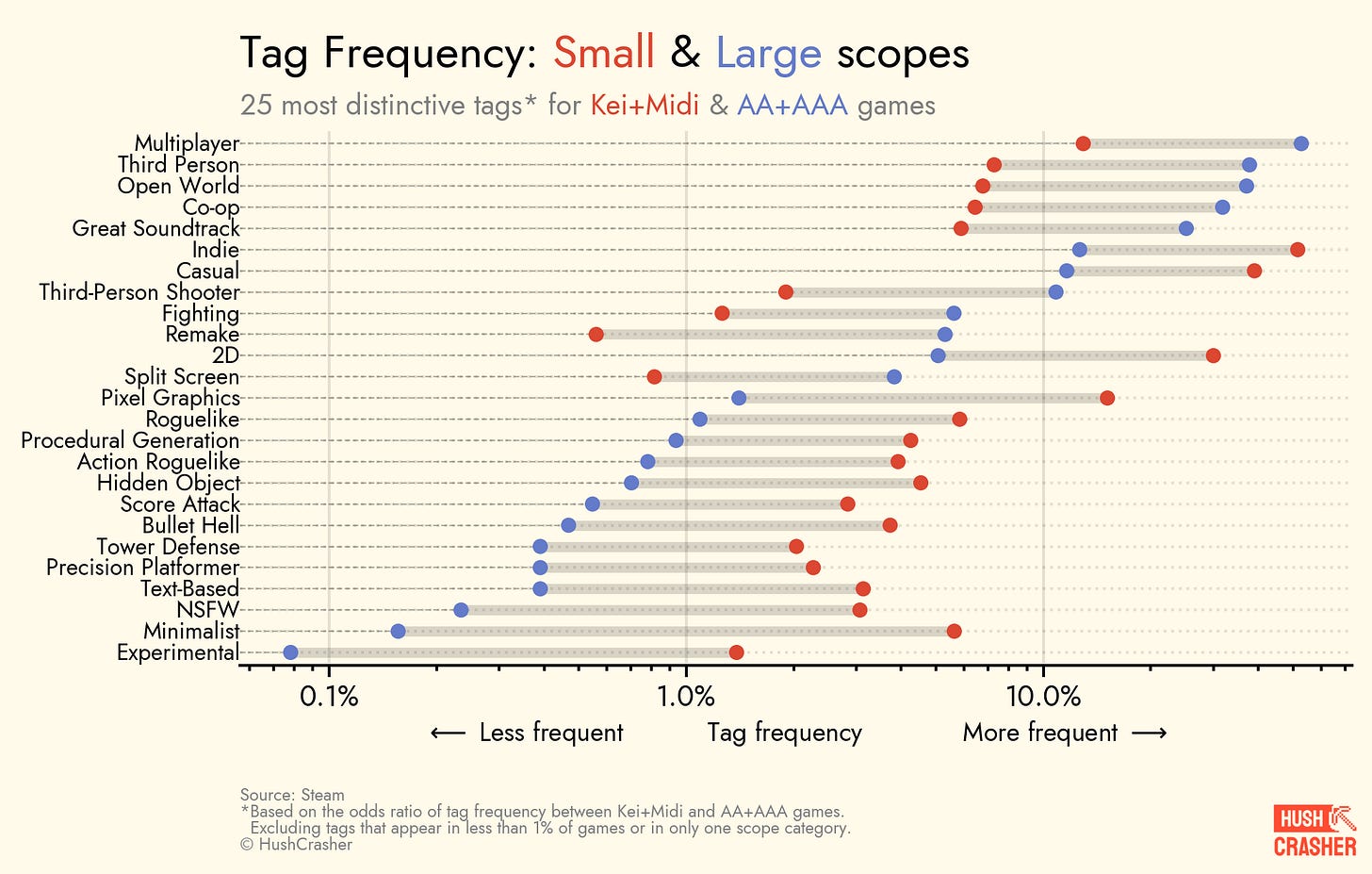

A game's scope inherently dictates its genre possibilities, which means that by setting that scope, developers often tie their hands creatively. A Kei open-world would be a suicide mission, while hiring thousands of people to create a simple 2D platformer may be interesting, but would certainly be a money pit.

One way to gauge these differences is to look at the game tags that are over-represented or under-represented within each group. This reveals the usual suspects: 'Multiplayer' and 'Co-op' are common for A-games (AA and AAA) while '2D' and 'Pixel-Graphics' are distinctive of smaller scopes. This makes sense from an economic perspective, as the latter are much cheaper to make than the former. However, recent multiplayer Kei-hits such as Lethal Company and Peak might be a turning point.

The choice of scope even goes so far as to influence the type of creative risks a developer is willing to take. For instance, 3% of Kei and Midi games have the 'Experimental' tag, which is almost completely absent from A-games. Meanwhile, 'Remake' accounts for ~5% of premium games - larger studios, with more at stake, often prefer the safer bet of a known success.

AAAs cost 10 times more than AAs

What’s the one thing we can’t leave out when talking about game scope? The budget. It’s time to talk numbers. In our next article, we focus on how much it costs to make a game. Subscribe to our newsletter to be kept updated when new article comes out!

Hopefully it won't go any further than that because AAAAA is already taken by our lovely French Andouillette.

As a quick side-fact, even classifying game genres is still an unsolved issue in academia. See this meta-analysis.

Mathews, C. C., & Wearn, N. (2016). How are modern video games marketed?. The computer games journal, 5(1), 23-37.

*SUPER* Interesting Analysis! I love this approach. While I don't think the value of *~vibes~* will ever be completely irrelevant to these distinctions, providing a quantitative classification like this should absolutely be a sanity check *at least* and it's great to finally see one!!

This was so exciting to me that I put on my journal club hat, and I have a few follow up questions. Apologies for going obnoxious academic mode!

1) Would love to know more about feature importance and see a list of all the features used in your PCA analysis. If game size/credit count are most important, how much less important was your third feature? Game length is quantitative and seems super relevant to classification from a *~vibes~* perspective, curious where that fell in feature importance? (I love the SHAP technique for feature importance, but that's me)

2) if k-means preferences spherical clusters, what if less-spherical clusters yield a better fit? That would likely mean using a different k-optimization score, but would be super curious to see-- can we identify a III cluster and prove that it's a real phenomenon?? If you used DBSCAN/Davies-Boudin instead of k-means/CH, do you get more clusters?

3) There is so much variance in log game size vs. credit count goes down-- totally makes sense, smaller game = optimization is less important and you have fewer people to do it. Is there potentially some additional meaning you could get out of that spread? Does a low credit count/high game size mean anything? Is there another feature that gets more important as the size/credit count correlation starts to fall apart?

4) now this one gets political-- I wonder if country of origin has a meaningful impact on this classification. Do countries with better labor laws require more people to make them, thus skewing them towards midi/AA when the vibe is more kei/midi? What if you encoded county of origin as its World Justice Index. I wonder if that has a meaningful negative correlation to the cluster number?

5) like other comments already say, would love a publically available dataset ❤️

Super excited to read about the game budget prediction model!!

Very interesting!

I also feel like AAA of yesterday are not AAA of today. Today for example a small team could remake an Ocarina of Time with a vastly inferior budget, which I imagine can interfere with the dataset.