How much does it cost to make a video game?

We built a model to estimate the budget of 100,000 games. Here's what we found.

Even in a creative industry, cash is what keeps the lights on. Game budgets are key to tracking the market’s dynamics—from macro trends to the actors within.

Yet, this is one of the hardest data to get. Everyone is quick to talk about sales (especially when glorious). There are even widely-known models to predict a game’s sales from Steam reviews. The budgets needed to make those games, however, often remain the greatest unknown in the equation. You’ll find no budgets database, and very few public announcements.1 All you’ll find are rumors and whimsical estimates.

No wonder this topic stirs up such a great passion among players and professionals.

Players love sneaking this data on forums and subreddits: they are eager to judge a game’s value-to-budget ratio and compare spending across games.

As for professionals (developers, publishers, investors), they crave benchmarks. “How do other studios handle this?”, “What genres are the most budget-demanding?”.

So, everyone wants to know! Yet, no one knows. That’s what motivated us to create HushCrasher 1 year ago. True to our mission, we used data science to predict the budget of all games on Steam. Here are our results.

Making a budget prediction model

Where does this budget data come from, you may ask? That’s a fair question because finding reliable budget figures is a hell of a hard task. Sources are scattered, journalists relay ballpark estimates; and half of the time, you won’t know if marketing is included (which can double the budget for AAA).

This is part of our Budget 101 series, breaking down the costs of making games.

That did not stop us. We spent weeks scavenging web archives, news articles, data leaks, post-mortems, and forums. We also consulted some industry contacts, who generously—and confidentially—agreed to share their financial data.

But that wasn’t enough. Our dataset was nowhere big enough to draw direct conclusions about industry-wide trends. Good news is, there was light at the end. Our dataset was big enough to train a machine learning model that would generate budget estimates for every single game available on Steam.

To make our results as precise as possible, we needed to feed the model with predictors of costs. We aim to protect our ‘secret sauce’ but here’s a taste of some key ingredients: credit length, publisher’s and studio’s experience, variety of distinct job titles, supported languages, and dozens of other variables.

For such a complex task, our model achieves a high level of accuracy, predicting the actual budget within a 10% margin, on average, for now.2

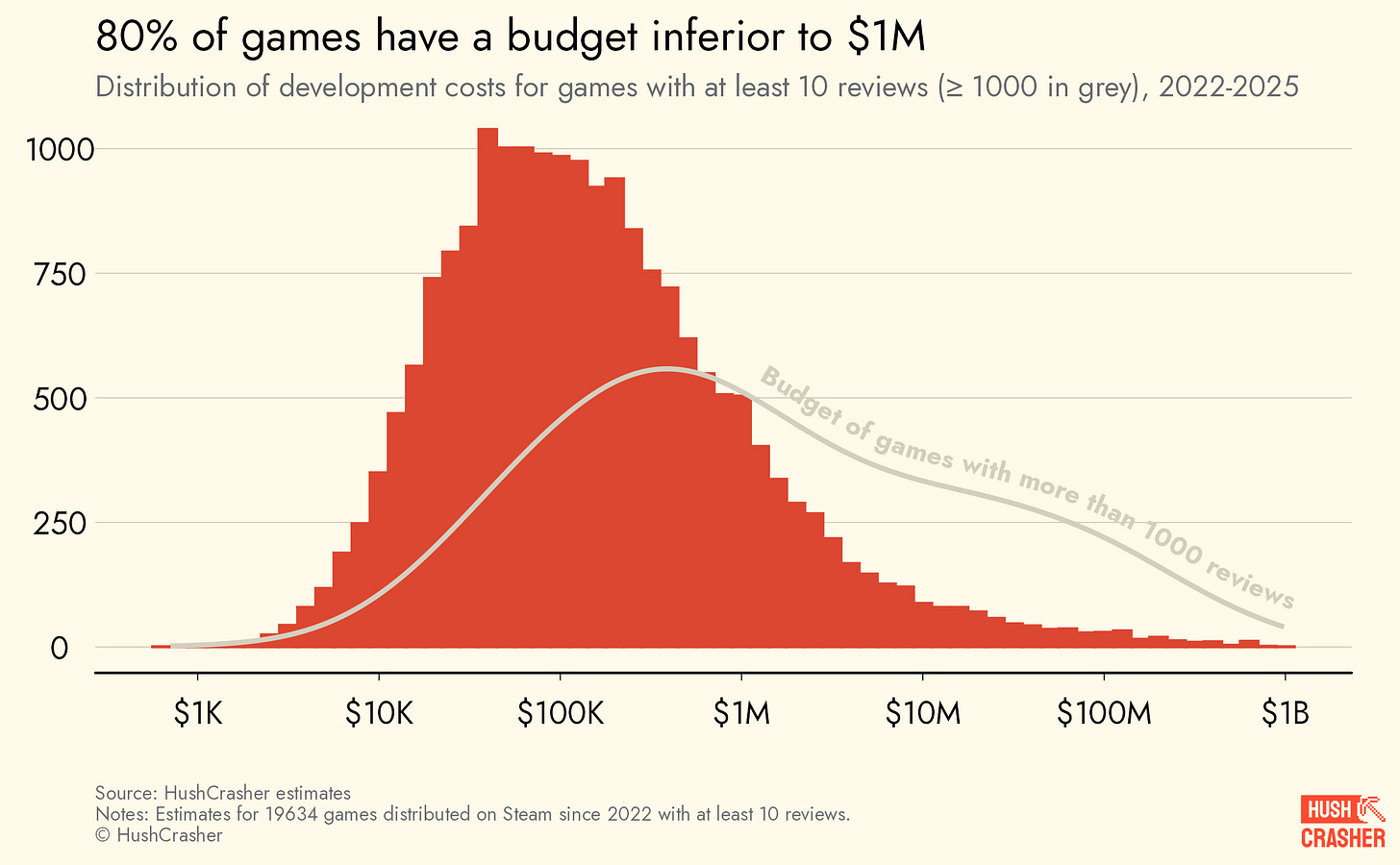

We ended up with budget estimates for around 100,000 games. In this article, we present our results for the recent period of 2022–2025 and exclude games with fewer than 10 reviews. This leaves us with 19,634 games.

We owe this data to the generous developers who shared their figures. If you believe in our mission to give a better understanding of the industry, please join our effort! Submit your game budget information here. Security first: your figures will be protected by an NDA, ensuring they’ll never be shared or sold.

Tell me your scope, I’ll tell you how much you’ll spend

If you’re not familiar with Midi and Kei, check our previous article where we explain how the common categorization (indie, III, AA, AAA) was flawed, and why we had to make a better one.

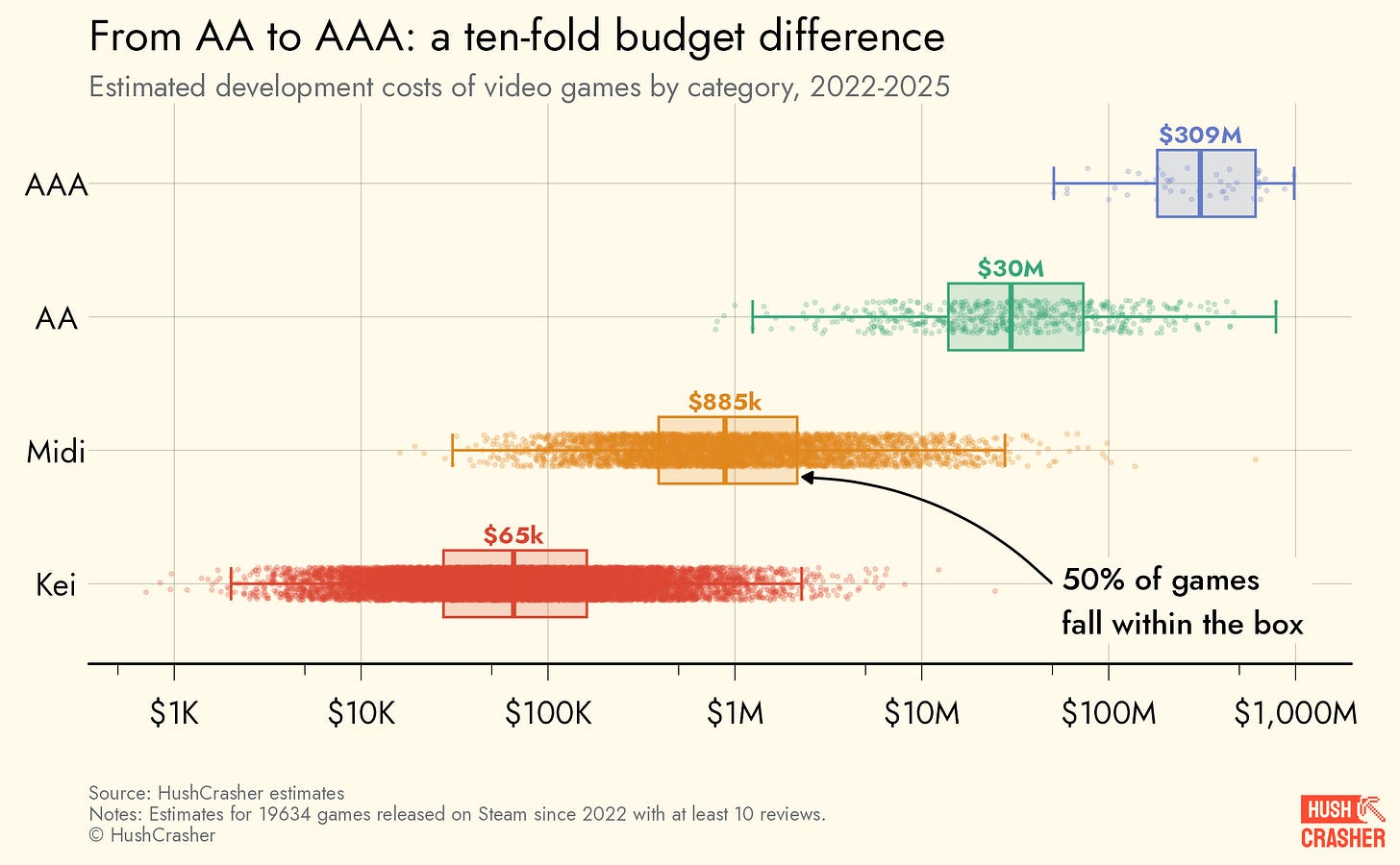

Kei game developers clearly know how need to keep costs low—half of them do it for less than $65k. This mainly reflects developers’ cost of living and location. Braid, for example, costed $200k because its developer, Jonathan Blow “didn’t want to live in a shack somewhere“. Meanwhile, Eldritch, the 2013 Lovecraft inspired FPS cost a total of $22k. Its developer David Pittman also explained that “the primary cost [...] was the burn rate of my own living expenses [...]”.

As for Midi games, their budget box might look like they’re chilling with the Kei one, but don’t be fooled—that overlap only concerns the data points outside the 75th percentile. The medians show the real story: making a Midi game is actually 14 times as pricey as a Kei game.

Indeed, cost is doomed to increase with a larger team and proper company structure. For instance, Thimbleweed Park—a 2017 point-and-click—ended up costing no less than 1M$ according to Ron Gilbert.

Stepping up your scope will scale your costs exponentially: the median cost of AAs is 33x that of Midi games, and the AAAs is 10x that of AAs. With games getting more complex, it’s no surprise that Black Ops Cold War cost $700M, almost 9 times the $82M already required for Spider-Man: Miles Morales.3 While it hasn’t always been the case, AAA games now fully rival the biggest US cinema blockbusters. It’s even fair to say they now go far beyond it.

Engine War

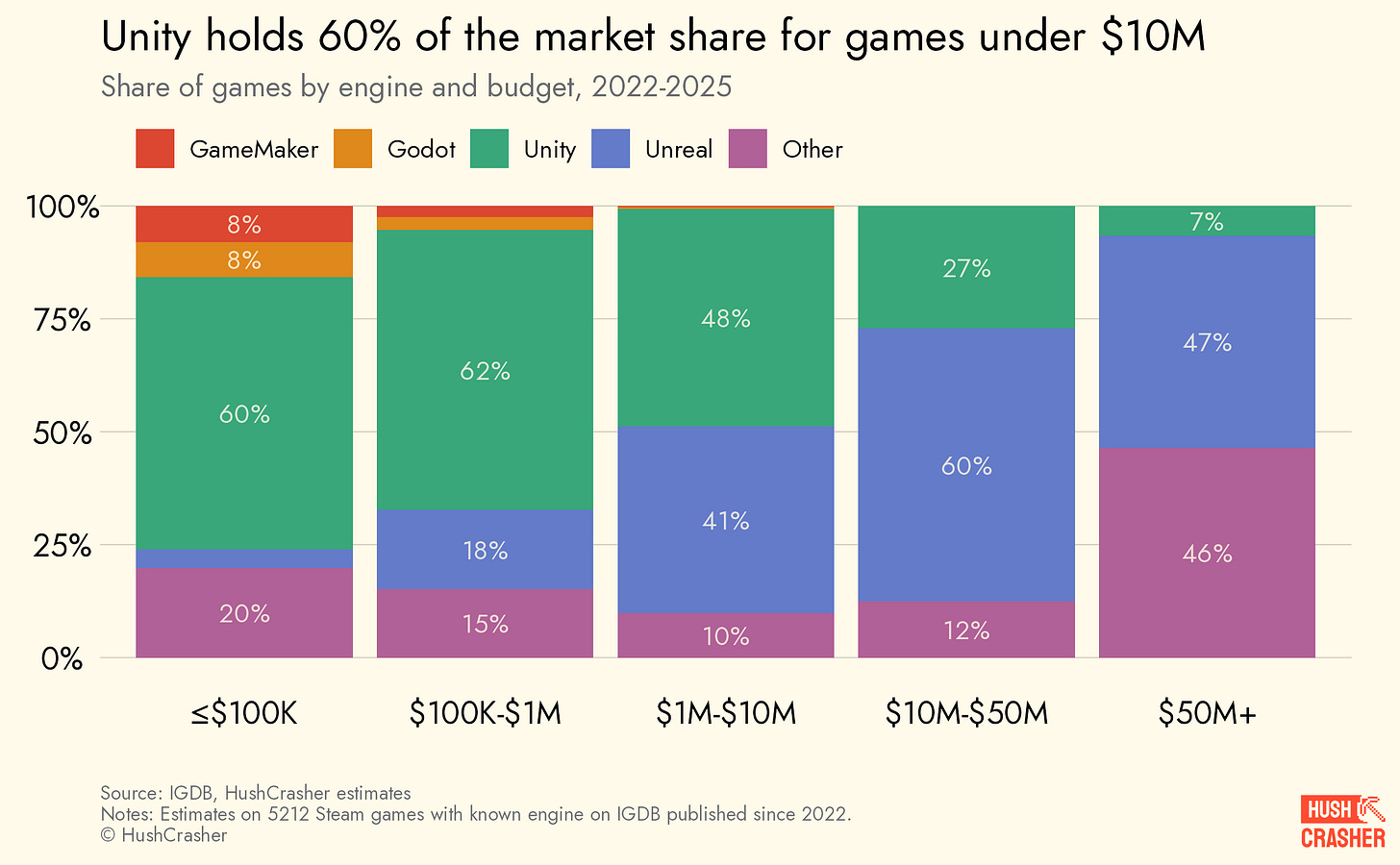

It’s stunning that Godot is one of Unity’s biggest challengers for small-scope (<$100k) games. It’s David—the open-source tool—against Goliath, the billion(!)-dollar financed software. It’s fair to say that David got a booster in 2023 when Unity changed its pricing model. While it was fully reversed barely a year later, the trust was broken, and it gave a lasting bonus to Godot, now on the edge to overcome GameMaker.

For Unreal, the cliché that it’s mainly for large projects still holds true. Kei successes like Manor Lords might convince other. Currently, Unreal leads the high-budget game market, holding more than half of its share.

The true challenger to Unity and Unreal resides in the “Other” category. For projects with small budgets, it’s a diverse array of open-source solutions and custom engines. Conversely, at the high end, “Other” mainly defines proprietary, in-house engines—like Rockstar’s RAGE, Bethesda’s Creation Engine (though they transitioned to Unreal for the Oblivion remaster), or the impressive Decima Engine from Guerrilla Games.

The cost of (creative) freedom

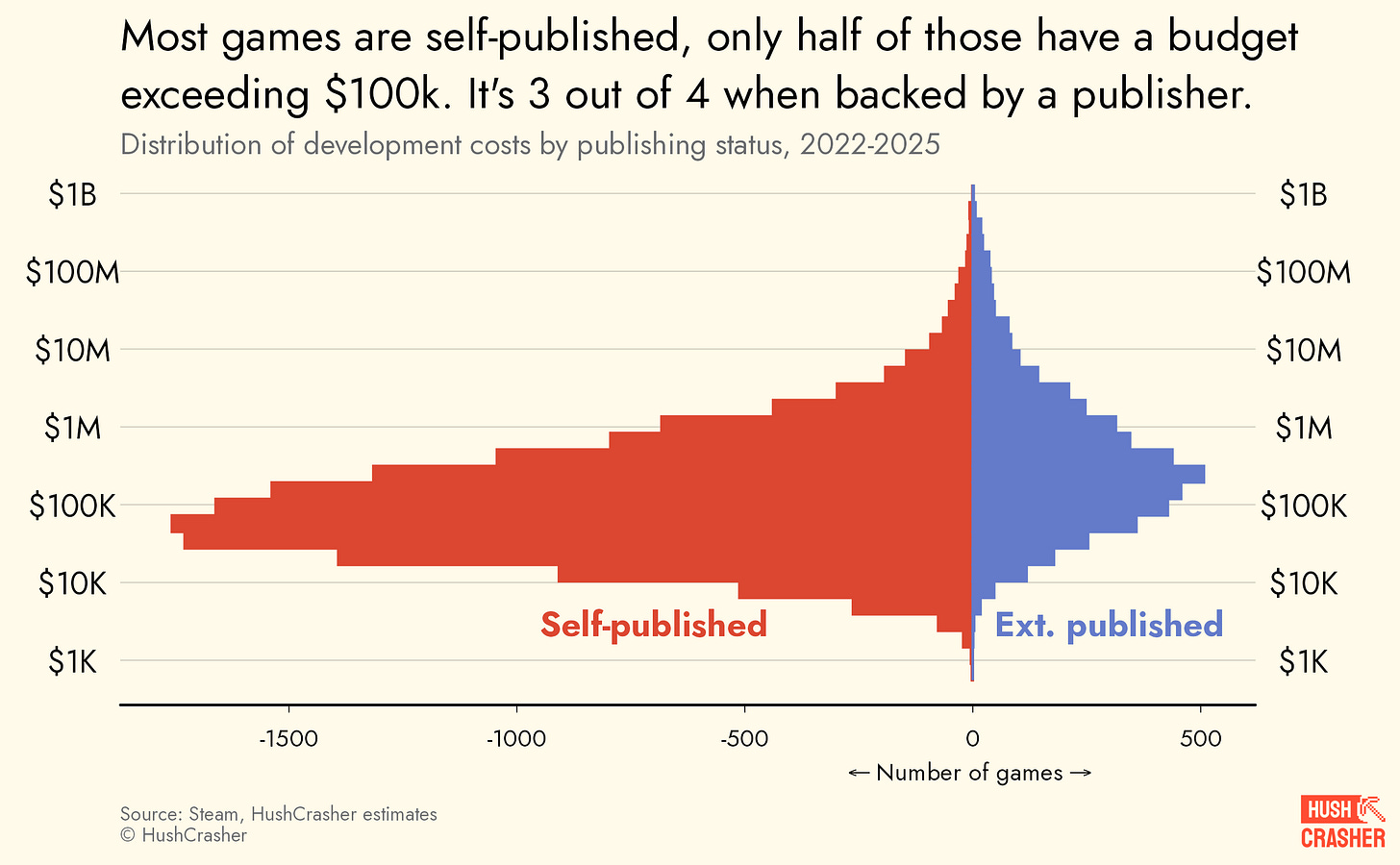

Partnering with a publisher is rarer than you might think: only 23% of developers do so. When they do, it’s more than just shifting costs from self-funding to external finance. Ultimately, it results in a higher development budget, x3 to x4 on average.

This increase could mean several things:

The spending jump may not reflect only a step-up in the final scope, but also a drop in resource investment efficiency: Publisher money might be invested less efficiently than developers’ own capital, this is known as the principal-agent problem.4 Or it might be the inevitable added cost of a professional relationship (meetings, reporting, having to justify why this step is late on top of already being late, etc.).

This extra money could be the necessary investment to achieve a successful game. Does it? We’ll have to cross-check this against commercial success metrics. Count on us.

2D to 3D: a dime’s worth difference?

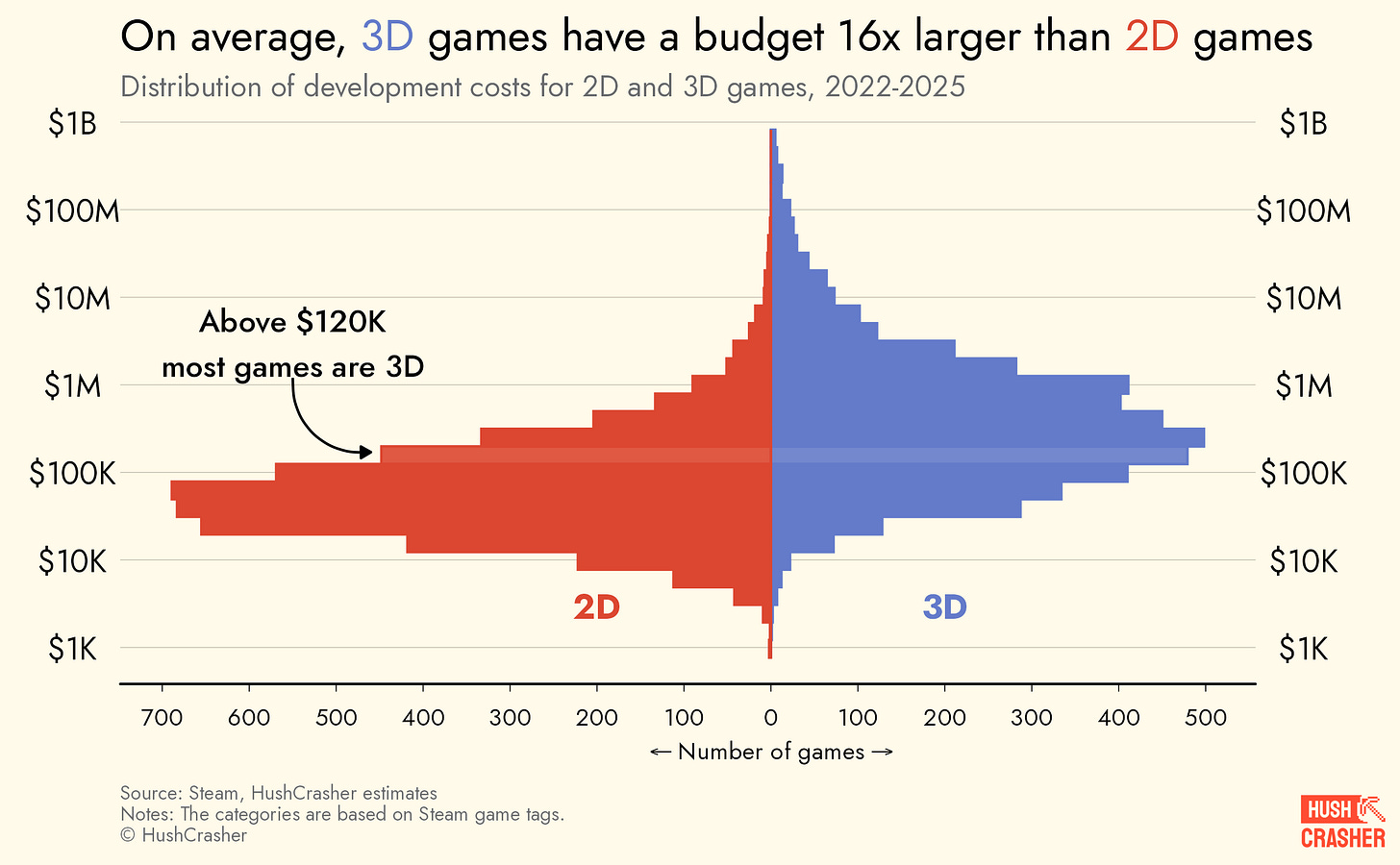

Making 3D games might have been impossible for small teams in the past, but it’s no longer the case. We now see 3D games of all budgets, from PSX stylized horror Kei to ultra realistic AAA. The large average difference in cost (3D games are 16 times costlier!) is mainly because 2D games rarely get past over $1M budgets.

A multi(player)-million dollar business

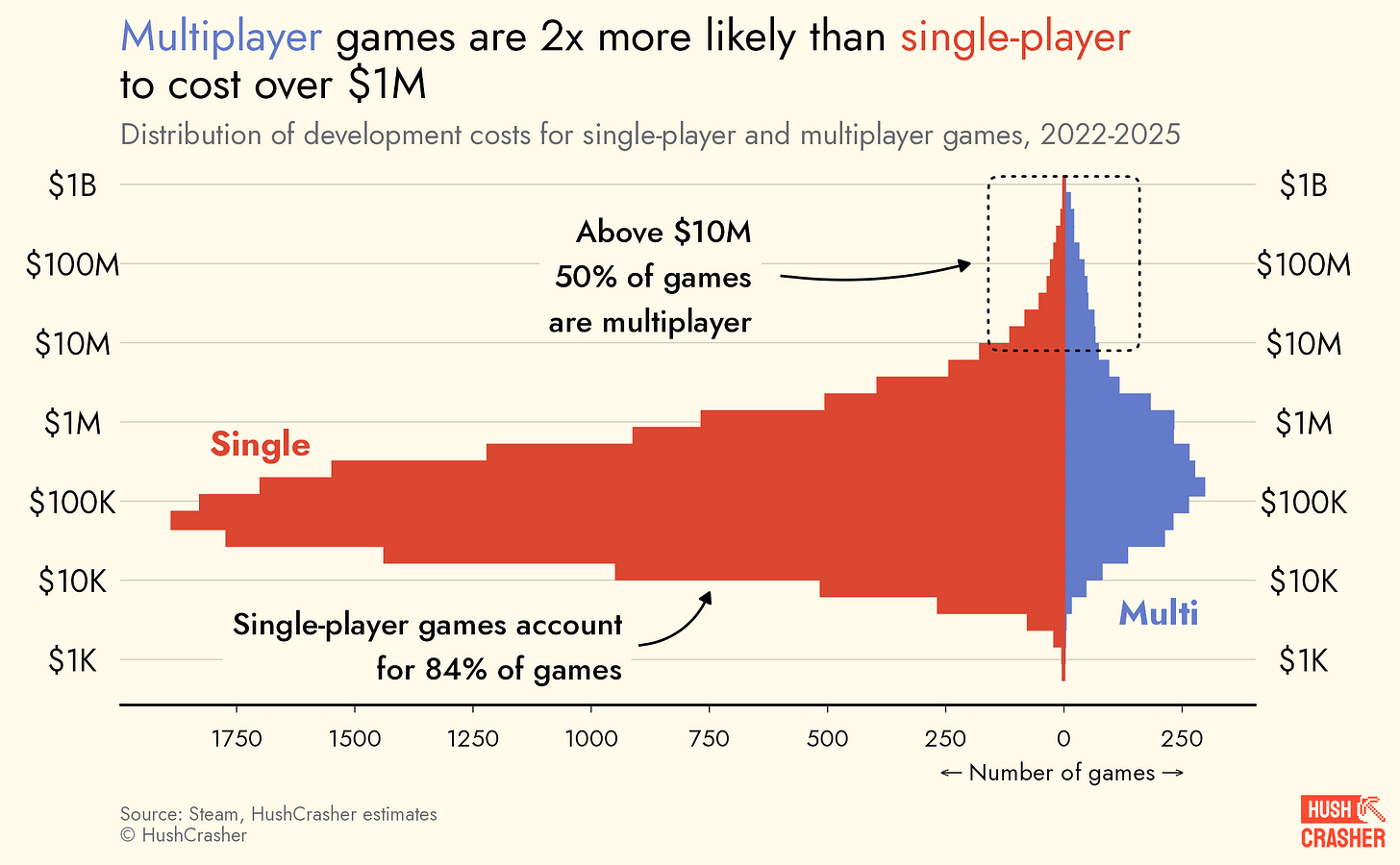

However, multiplayer games are more likely to break the million-dollar mark. While they account for only 16% of all games, they make up half of the market for budgets above $10M. This gap highlights how single player games are relatively scarce for big studios.

Conclusion

Here is a snapshot of today’s budget. Now, to get a complete picture of this subject, there’s still a lot to investigate.

First, we could wonder how those budgets have evolved over time. Have game budgets really skyrocketed over the years like everyone says? And did it concern all games or just a specific category?

Secondly, besides correlations, it would be interesting to know how creative and technical decisions impact costs. How much does a budget increase when making it 3D vs 2D? How much more does each new team member really cost in the end? Is the marginal cost of a team member stable as the game size increase?

Finally, the budgets can differ greatly between countries, and it might be insightful to look back at those figures knowing where the people behind those games are based.

Those are all food for thought, and might be the topic of our next articles, so don’t forget to subscribe if you want to stay updated.

Developers’ quietness about budgets is somehow understandable. First, no one wants to be publicly judged on its efficiency, especially in a creative sector. This isn’t like cranking out widgets on an assembly line; costs can vary wildly for the same scope because the creative process is inherently chaotic and unpredictable. Secondly, it can be tough for small (often non-business) teams to track everything budget-related. For Kei game developers paying themselves from their savings, the concept of a budget can even feel meaningless. Finally, and this goes without saying, it’s also due to ༺ 𝒷𝓊𝓈𝒾𝓃ℯ𝓈𝓈 𝓈ℯ𝒸𝓇ℯ𝒸𝓎 ༻.

The 10% corresponds to the mean average percentage error (MAPE) on the test set.

When you exclude the astonishing $106M license fees to Marvel!

The principal-agent problem describes the conflict of interest between the developer (the agent) making the game on behalf of the principal (the publisher). When the developer has a small profit share and is spending the publisher’s money, it has less inventive to spend if efficiently. To align interests, contracts may include a better profit share, or more surveillance and control.

The pricing debacle really exposed Unity's vulnerability in the low-budget segment where switching costs are minimal. Godot's momentum feels almost irreversble now, even after Unity walked back the changes. The trust issue runs deeper than just pricing its about whether devs can bet their entire project on a platform that might shift the rules midway. Unity's dominance in the sub-$100k tier is clearly eroding faster than anyone expected.

The budgets of games with more than 1000 reviews is looking a little bimodal, i wonder if it would be possible to break the distribution into the two distributions and what kind of games end up in each distribution.